TL;DR: I embarked on building a prototype for an audio DSP to control speaker systems from scratch. However, my limited knowledge of the Rust language and low-level programming prompted me to start over.

The Idea

I have a deep passion for music, particularly in the electronic genres, and even more so for high-quality sound systems that bring this music to life. Consequently, while working at events and organizing parties with my friends, it dawned on me that I needed an Audio DSP (Digital Signal Processor) in my toolkit to fine-tune speaker systems to my liking. For those unfamiliar with it, an Audio DSP is essentially a specialized computer tailored for applying sound-shaping algorithms to a signal. You can place it between a source (such as a phone or DJ Mixer) and a speaker system. This allows you to shape the signal precisely, correcting loudspeaker errors, and creating a coherent sound system by combining different speakers.

In the summer of 2022, I purchased a robust DSP, the dbx VENU360, and constructed a 19" rack for it while eagerly awaiting its arrival. However, my plans were derailed by the chip crisis, receiving a notification that the DSP wouldn't be shipped that year — indeed, it's still unavailable as of today.

At the same time, I delved into the underlying technology of DSPs and discovered that they use specialized CPUs that can do signal processing very well, but nothing else particularly good. Most DSPs have a fixed processing chain, offering reliability but limited flexibility. While some DSPs are more flexible in that regard, they often require you to compile your processing chain into machine code and upload it to the hardware—a cumbersome process, especially in high-pressure concert environments.

These constraints made sense when DSPs were first used in speaker systems in the last century. However, today's computers boast virtually unlimited processing power. Also, with more processing power, more advanced sound shaping algorithms can be employed.

Using a DAW (a software for music production and processing), you can easily route your audio into a standard computer and apply any sophisticated processing chain in real-time. I tested this with a ten-year-old iMac in my living room, and it works seamlessly. I still wouldn't use that kind of setup in a live venue, because the used soft- and hardware are not made for that purpose. Therefore, it is somewhat inconvenient to use and doesn't give you any guarantees about reliability.

So yeah, I'm a software developer and I want a powerful DSP. The challenge is on!

The Goals & Tech Stack

Realistically, it's not feasible to create a fully polished product like this on my own within a reasonable timeframe, so my objective is to develop a minimal prototype.

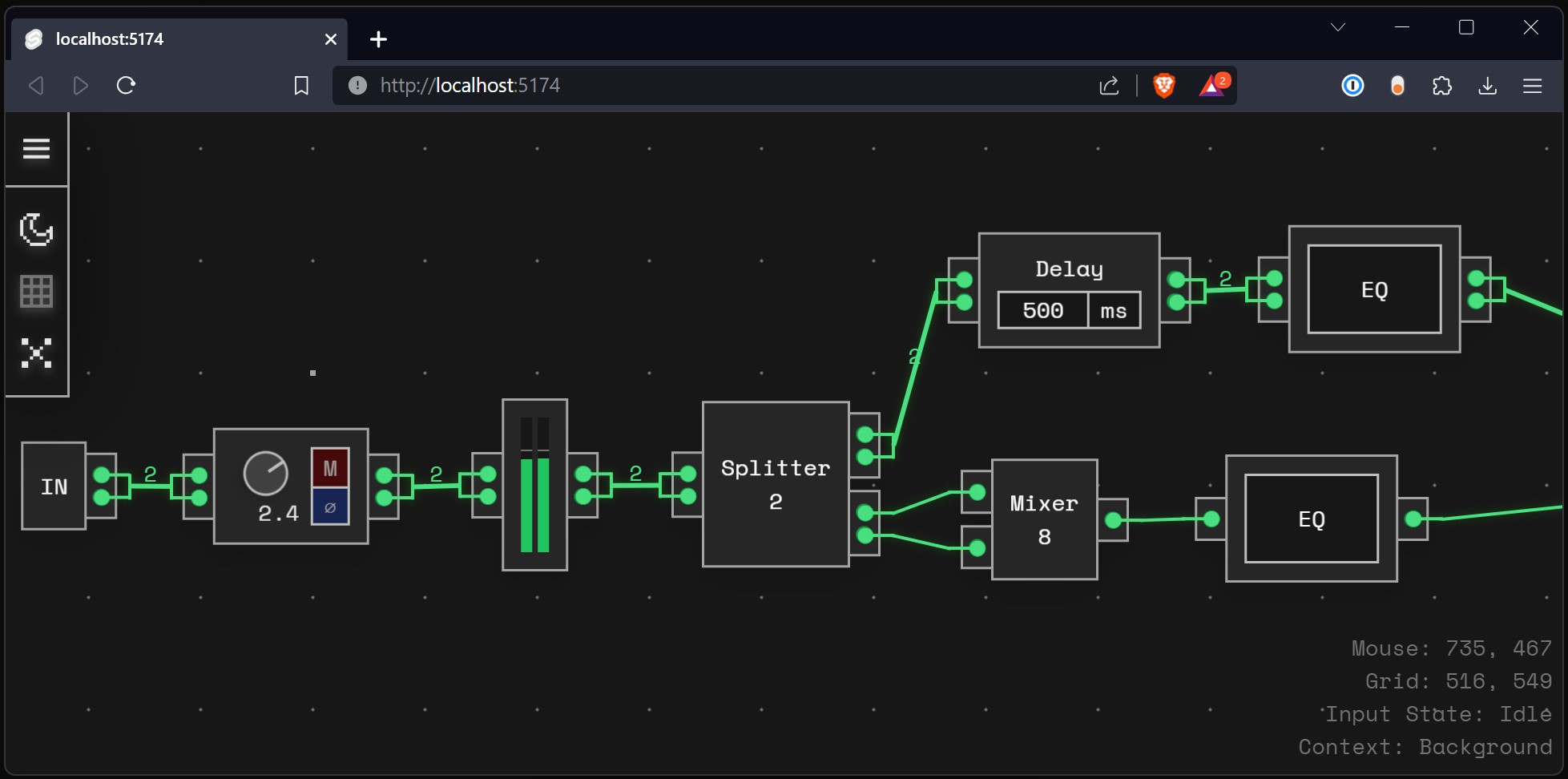

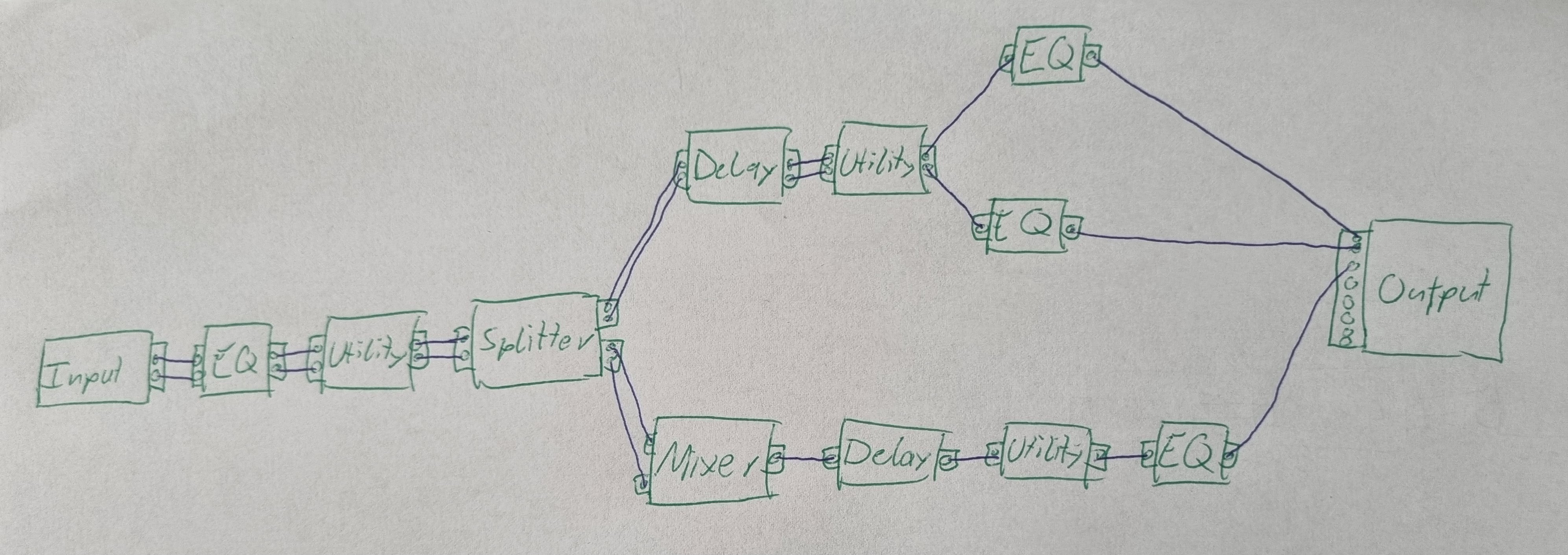

I opted for a node-based processing chain, where each processing step is a node. You can add and connect nodes as needed.

One of the fundamental challenges is real-time processing: In a typical application, the DSP has 0.8ms to process the current signal. If it were to take any longer even once, the only thing you'd hear are ugly loud clicking noises. To ensure real-time processing, I use a real-time patched Linux, which grants the software any processing power it needs right away, disregarding anything else that runs on the computer. For low-level control over the machine, I selected Rust as the programming language.

The device can be connected to a network (via Ethernet or Wi-Fi) or host its own network. It features a web server providing a user-friendly control interface, allowing you to adjust settings by simply opening a website on your laptop or phone. No more dealing with outdated control programs that only run on Windows XP!

As a hardware foundation, I employed a Raspberry Pi for its ease of use. In the future, more specialized hardware can be used. The Raspberry Pi is paired with a Behringer UMC1820, providing audio inputs/outputs and analog-to-digital/digital-to-analog conversion. While this setup introduces some latency (~30ms), which is unsuitable for a production system, it suffices for my current needs. The latency could be avoided by building a custom sound interface directly connected to the GPIO pins of the Pi, but I'm not an electrical engineer, so the Behringer must suffice for now.

Implementing & The Point of Failure

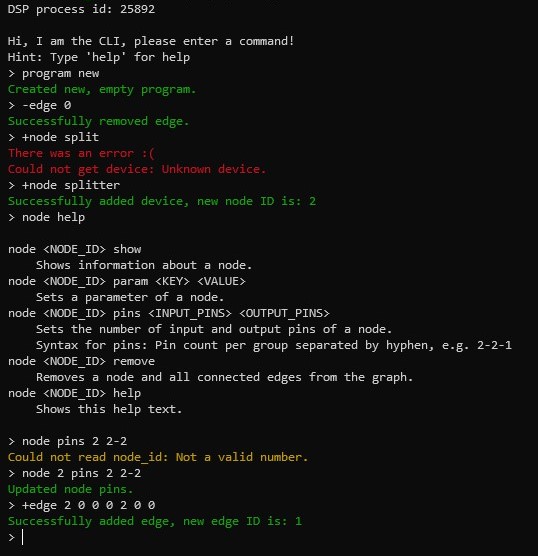

So I got started on implementing. I started with the engine, and along the way I learned a lot about Rust, real-time programming, graph algorithms, concurrency and much more. After a few months, I had a functional engine. However, without a frontend, the only means of controlling it were via savefiles or an interactive CLI.

As a demonstration, I created a signal chain for my desk speakers - and it actually worked. A huge success!

Concurrent programming presented the most significant challenge during implementation. How could I modify the processing chain externally while the engine continued its work uninterrupted? While sophisticated (albeit complex) paradigms exist for this problem, I opted for the naive approach of using mutexes initially. Mutexes ensure that only one part of the program accesses the processing chain at a time, making other parts wait. However, this approach contradicts the real-time principle, as the engine shouldn't wait for another thread to write changes while processing within the 0.8ms window. Nevertheless, for minimal changes, it sufficed for the moment, allowing me to tackle other challenges.

Subsequently, I ventured into frontend development—an interactive webpage hosted by the engine, enabling users to drag and connect nodes freely. I decided on SvelteKit as a framework, simplifying the transformation of standard HTML markup into a highly interactive application that resembles a video game more than a typical web page. After a few weeks, I achieved live, user-friendly control over many aspects of the processing chain.

I then tackled the challenge of visualization, creating live dB meters displaying current amplitude, frequency graphs, and more.

As you can see, I got that to work as well, but here the problems started to arise: In order to visualize with 60 FPS, you'd have to access the processing chain 60 times a second. My initial mutex implementation proved inadequate, resulting in an unresponsive UI. Additionally, my limited knowledge of organizing data structures in concurrent programs led to race conditions that occasionally crashed the engine.

At this point, it became evident that the engine's codebase had significant flaws, rendering further development impractical. After all, I was learning the language while coding, simultaneously grappling with various low-level paradigms. Consequently, the codebase ended up far from ideal.

What's next

The time has come to start anew. I will rebuild the codebase from the ground up, this time with a well-structured architecture from the outset. Although it's somewhat disheartening to bid farewell to the old engine, I don't consider the eight months I spent on the project wasted. It was an invaluable learning experience and a lot of fun.

I intend to document future developments in more technical blog posts.

Thank you for reading!